The Tripitaka, or the “sutras in three baskets,” was compiled twice during Goryeo. The compilation of the first edition began in 1011, the second year of King Hyeonjong, and was completed in 1087, the fourth year of King Seonjong. The project lasted for 76 years through six reigns. However, the Mongol invaders burned the printing blocks in 1232. Compilation of the second edition began in 1236, the 23rd year of King Gojong, and was completed in 1251, the 38th year of Gojong. This second edition is the Tripitaka Koreana, which is known by the Korean name Palman Daejanggyeong (The Great Collection of Scriptures in Eighty Thousand Blocks) or Goryeo Daejanggyeong (The Great Collection of Scriptures of Goryeo).

Initially, the printing blocks of this second edition were kept on Ganghwa Island, the seat of Goryeo’s wartime government. Later the woodblocks were temporarily moved to Seoul when the island became a frequent target for Japanese marauders and then in 1398, the seventh year of King Taejo of the Joseon Dynasty, to Haeinsa Temple, where they have been kept until today.

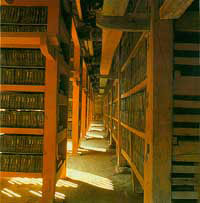

Depository in Mountain Monastery

Haeinsa Temple, built in 802 during the Unified Silla period, is nestled on Mt. Gaya in Hapcheon, South Gyeongsang Province. Since its founding Haeinsa has been recognized as one of Korea’s leading Buddhist monasteries. Particularly, it is known for representing one of the “three jewels of Buddhism,” that is, the Buddha, the Dharma (teachings of the Buddha), and the Sangha (community of monks who deliver the Buddha’s teachings). As it houses the Tripitaka, a collection of the Buddha’s teachings, Haeinsa is appropriately called the “Temple of Dharma.”

The storage buildings for the Tripitaka Koreana are located on the highest temple grounds. The site is highly symbolic in view of the fact that the hall of the Buddha usually sits at the highest and most important spot on most other temple compounds. Moreover, Haeinsa keeps the printing blocks in perfect condition. Since wood is vulnerable to fire, moisture and insects, it is incredible that all these blocks have been successfully preserved, without a single piece showing signs of decay or warping, for the past seven and a half centuries. What is the secret behind this miraculous feat?

Though the printing blocks were also made with special care to endure time and the elements, the storage buildings are the first true wonder. Tripitaka Koreana is known as the world’s finest extant Buddhist canon in Chinese script but its depository, the only one of its kind in the world, is a no less wondrous achievement of medieval science and technology.

Fires and Wartime Destruction

Haeinsa had seven fires between 1695, the 21st year of King Sukjong, and 1871, the eighth year of King Gojong of Joseon, but the Tripitaka archives remained completely unscathed, embellishing the mystery surrounding the seemingly simple wooden buildings.

It is not known exactly when the two storage buildings, named Tripitaka Hall (Janggyeonggak), were constructed but they are evidently the oldest structures of Haeinsa, preserving the simple beauty of the wooden architecture of the early Joseon period (1392-1910). Historical records say that 46 kan, or inter-columns bays, of the archive buildings were reconstructed under orders of King Sejo in 1457, the third year of his reign. Some 30 bays were repaired with support from the royal family in 1488, the 19th year of King Seongjong. One of the two buildings, named the Storage of Sutra (Sudarajang), was repaired in 1622, the 14th year of King Gwanghaegun; the other building, named the Hall of Dharma Jewel (Beopbojeon), was repaired in 1624, the second year of King Injo.

The Tripitaka depository faced yet another crisis during the Korean War of 1950-1953. The area around Haeinsa was among the fiercest battlegrounds during the internecine armed conflict. The South Korean and U.N. forces bombarded the area many times to suppress the North Korean guerrillas hiding in the mountains after being left behind by a troop withdrawal. However, the temple and the Tripitaka were miraculously saved from being reduced to ashes, thanks to people who appreciated their value.

The hero now admired for his “righteous disobedience” is Air Force Colonel Kim Young-hwan. Colonel Kim was ordered to destroy Haeinsa during the anti-guerrilla campaign in September 1951. He led his squadron of jet fighters flying over the area but decided not to drop a single bomb. Kim later said during an investigation that he could not burn the nation’s invaluable cultural treasures in order to kill a few communist guerrillas.

Scientific Design Utilizing Natural Conditions

The depository buildings for the Tripitaka Koreana were designed to take maximum advantage of the topography of the terrain. Resting on the highest area in the temple grounds, at 655 meters above sea level on the middle of the slope of Mt. Gaya which is 1,430 meters high, the elongated wooden pavilions face the southwest so as to receive sunlight for long hours - 12 hours a day in the summer, nine hours in the spring and the autumn, and seven hours in the winter. No parts of the buildings are in permanent shade. Thus they prevent the woodblocks from getting moist or from decaying, and they keep out moss, mildew and insects.

The depository consists of four buildings - the two Tripitaka archives sitting back to back with a rectangular courtyard between them, and two annex buildings standing on either end of the courtyard. The northern building is the main archive named the Hall of Dharma Jewel, and the southern building is the Storage of Sutra. The two small buildings facing the courtyard keep printing blocks for scriptures and other books published by the temple.

The Tripitaka archives are both 60.44 meters long, with 15 bays on the front and two bays on the sides, and have hipped roofs. They are simple wooden structures with no decorative elements other than vertically grilled, open windows. These windows are the core devices displaying the ingenious creativity of the medieval architects.

Both buildings have two rows of wooden grill windows on the front and back walls divided by a central molding. The windows differ in size, which is the essential wisdom behind the efficient adjustment of air flow and sunlight ensuring maximum ventilation, temperature and humidity control.

In the case of the Storage of Sutra in the front, for example, the windows of the lower row on the front wall are about four times larger than those of the upper row, while the upper windows on the back wall are about one and a half times the size of the lower windows. In the case of the Hall of Dharma Jewel to the back, the lower windows on the front wall are approximately 4.6 times the size of the upper windows, and the upper windows on the back wall are about 1.5 times the size of the lower windows.

This is apparently a plan based on the theory of hydrodynamics and air flow. The windows allow for maximum natural ventilation; fresh air is brought in through the large upper windows to circulate around the hall before escaping through the windows on the opposite side. The small lower windows on the back wall keep moisture from seeping in from the ground outside. Furthermore, the back windows of the Hall of Dharma Jewel slightly differ in size from bay to bay. This also seems to be a design element utilized to maximize the hall’s conservatory function based on empirical judgment. However, modern science has yet to answer precisely how.

Another secret rests in the floors of the depository halls. Built upon thin granite foundations that facilitate smooth drainage, these buildings have clay floors with thick layers of salt, charcoal and lime underneath, which absorb excess moisture during the summer rainy season and maintain an optimum humidity level by letting out the moisture during the dry winter months. The clay walls of the buildings also help enhance these functions.

Each hall has two long rows of five-level shelves with an isle in between. Each level of the shelves holds two rows of woodblocks, vertically placed one row upon the other with a little empty room on the top so the air can freely circulate. The printing blocks have thicker margins on the sides so the carved sections are always exposed to the air flow.

Thanks to all these considerations and devices, the temperature inside the depository halls can be maintained about 0.5 to 2 degrees Celsius lower than the temperature outside and the humidity can be kept 5 to 10 percent lower than the humidity outside. Even in dry spells the humidity inside the halls never falls below 40 percent.

The wood for Tripitaka blocks was processed through painstaking procedures to weatherproof the grain and retard decay. It was soaked in seawater for over three years, then cut into blocks and boiled in salt water. The blocks were then fully dried in the shade, exposed to the wind, before the surface was smoothed with a plane. Then the elaborate work of writing and carving began. After the text was engraved, each block was coated with a few layers of poisonous lacquer to repel harmful insects. Each corner was reinforced with metal clamps to prevent warping.

In recognition of its outstanding universal value as a legacy of medieval printing technology as well as unrivaled canonical content, the Tripitaka Koreana was placed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2007. The inscription of the depository halls came much earlier in 1995, a tribute to the prominent wisdom of ancient Korean architects and engineers that defies explanation by modern science.

The Tripitaka depository halls at Haeinsa epitomize the medieval science and technology that took maximum advantage of natural environments. The only buildings exclusively used for storing woodblocks for Buddhist canon in the world, the simple wooden structures pose many riddles to modern conservation science. |

>

>