perfectly preserved and veneration rites continue to be conducted in the authentic manner.

The cultural and religious origins of Jongmyo date to the Zhou Dynasty (circa 1046-221 B.C.) of China, or even earlier. Joseon based its state ceremonial systems on those of the Zhou as provided in The Rites of Zhou (Zhouli, or Jurye in Korean), but devised its own style and procedures in the actual construction of the royal memorial shrine and ceremonial performances. This is why Jongmyo is recognized as one of the outstanding cultural legacies of Korea.

The Sobering Beauty of Simplicity, Repetition and Restraint

The spirit tablets of kings and queens of the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), the last monarchy in Korean history, are enshrined in two halls on the compounds of Jongmyo: the Main Hall (Jeongjeon) keeps 49 royal spirit tablets and the Hall of Eternal Peace (Yeongnyeongjeon) keeps 34 tablets. The Main Hall has spirit tablets of those kings who command great respect and their queens, while the Hall of Eternal Peace has those of less worthy rulers as well as posthumous kings and their wives. Two of Joseon’s 27 kings, Yeonsangun and Gwanghaegun, both deposed due to misrule and demoted to prince, were denied the privilege of being honored in the shrine.

For the Joseon Dynasty, Jongmyo had symbolic intentions quite different from its palaces. It was the palace of past kings and queens, the sacred shrine of the royal family. Therefore, it is shrouded in a different ambience from the palaces. The solemn dignity and elegant serenity is due to the indigenous function of the shrine.

The halls and pavilions in Jongmyo, which are for keeping royal spirit tablets or preparing and performing veneration rituals, are simple and functional. They are typically devoid of ornate decoration in order to emphasize piety and solemnity.

The Main Hall, noted for its unique architectural style and solemn ambience, is the largest among contemporary wooden structures in the world, with the front facade running 101 meters along 25 bays. The impressivefacade of the Main Hall, with its imposing roof and a series of frontal columns, comes into view when one steps inside the south gate of its compound. The hall stands on a two-tiered stone platform that nearly covers the entire square courtyard. The broad stone platform, some 110 meters wide and 70 meters long, is covered with roughly dressed granite blocks. The elevated ritual arena is bright and open. Here the ritual officiants bow deeply and repeatedly and move in orderly processions while musicians and dancers perform during the royal ancestral rites.

The Main Hall, facing the expansive stone platform, appears austere and somber as if symbolizing the infinity connecting heaven and earth, and life and death. The thick round columns surmounted by a simple gabled roof form an image with soul-stirring appeal. The long series of identical columns and the horizontal roof ridge stretching in parallel with the ground symbolize the eternity of the royal lineage.

The Main Hall compound, surrounded with stone walls, has three gates. A brick-covered walkway runs through the horizontal stone platform from the main gate on the south to the Main Hall. The narrow path is reserved for the royal spirits so no living soul is allowed to tread on or cross it. The two other gates are for mortals: the east gate was for the king and the west gate for musicians and dancers. Even the king was no more than a humble mortal in this palace of deceased royal ancestors.

A stone-covered path runs straight north from the main entrance of Jongmyo toward the Main Hall compound. The path has three lanes: the raised central lane here is also reserved for the royal spirits and ritual offerings, and stretches to the Main Hall compound, while the lower side lanes for the king and the crown prince part from the spirit lane midway in the direction of the king’s pavilion on the right side. The king prepared himself for rites, bathing and dressing up, at the pavilion. The narrow path is covered with rough stones with fluctuating surfaces, so the king would walk slowly with his mind focused on the ancestral rites.

The construction of Jongmyo began in 1394, the third year of Taejo, when the capital was moved to Hanyang, and was completed the next year. Along with Changdeokgung and Changgyeonggung palaces, Jongmyo originally formed part of an exclusive zone in the heart of old Seoul. It now lies apart from the two palaces across a road, which the Japanese made to “cut off the vein of Joseon” during their colonial rule in the early 20th century.

Initially, the Main Hall had seven spirit chambers, flanked by a side chamber on either end. Frequent expansion was done to accommodate the spirit chambers of successive kings and queens, but the entire shrine was turned into ashes and the royal spirit tablets joined the king and the crown prince on their evacuation north toward Pyongyang when the Japanese invaded in 1592. The hall was rebuilt in 1608, the year Gwanghaegun ascended the throne, and again expanded several times. In 1836, the second year of Heonjong, the Main Hall attained its present scale with 19 spirit chambers, two side chambers each with three bays, and the corridors extended to the south from both ends.

The Hall of Eternal Peace is a smaller annex built to accommodate the growing number of royal spirit tablets. It was at first a six-chamber structure but attained the present scale with 16 spirit chambers in 1836, through repeated expansion and reconstruction. Though smaller, it basically has the same ground plan as the Main Hall and also has an elevated stone platform that covers almost the entire front courtyard. One distinctive feature is that the annex has four larger chambers covered with a taller roof at the center, while the Main Hall has an uninterrupted roofline and all of its chambers are of the same size. As a result, the annex has a somewhat comfortable feeling though not as majestic as the Main Hall, which is submerged in a stern atmosphere. The stone terraces in the backyard and the lush forest surrounding the compound add to the cozy feeling.

Neither the Main Hall nor the Hall of Eternal Peace faces due south but both are slightly tilted to the southwest. These royal memorial halls and all the other buildings for ritual preparations were situated to conform with the hilly topography so the natural contours of the land would not be destroyed. In contrast to the austere and functional structures of individual buildings, the overall ground plan of the shrine was designed to harmonize succinctly and beautifully with its natural environment. So the otherwise monotonous ritual spaces were endowed with pleasant vitality.

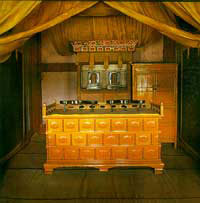

The two royal memorial halls are both long rectangular structures; they have a huge single space inside with cubicle-like spirit chambers lined along the northern wall. The royal spirit tablets are aligned in these chambers from west to east in the order of reign. With a two-panel door for each chamber to the front, all three other sides are surrounded with blind brick walls with no doors or windows. The halls are kept dark for the peaceful repose of the souls of the dead kings, but when rites are performed, the doors are opened and bamboo screens are hung over them.

An open front corridor runs the entire length of thefacade of both halls, providing an ideal space for rituals in all weather, and its shaded space gives depth to the halls and accentuates their solemn atmosphere as sacred abodes of royal spirits. The Main Hall has 20 entasis columns standing in a row, creating a magnificent view. The Hall of Eternal Peace was identically built but on a smaller scale.

Space for Communion between the Living and the Dead

The identical ritual tables set with carefully prepared food in glistening brass vessels and the same ritual procedures devoutly repeated by proud royal descendants dressed in ceremonial uniforms create a spectacle of classical elegance and formality during the royal ancestral ceremonies at Jongmyo, making one forget the daily routines of a modern society.

The stateliest rituals of Joseon, the royal ancestral ceremonies at Jongmyo were performed frequently around the year when the dynasty ruled Korea. They included the five major ceremonies for offering new harvest, held regularly at the Main Hall for each of the four seasons and toward the end of the year after the winter solstice. However, rites were held just twice at the Hall of Eternal Peace, in the spring and the autumn. These days, the royal ancestral rites are held once a year, on the first Sunday of May, under the auspices of the Jeonju Yi Clan Association consisting of descendants of the Joseon royal family.

A sequestered territory in the heart of a bustling metropolis, Jongmyo is comprised of more buildings than just the two royal memorial halls. They include the Hall of Meritorious Subjects (Gongsindang), the Hall of Seven Deities (Chilsadang), the Office of Ritual Affairs (Jeonsacheong), the Musicians’ Pavilion (Akgongcheong), the Royal Pavilion (Eosuksil), the Office of Incense and Ritual Supplies (Hyangdaecheong), and the Memorial Hall of King Gongmin (of the Goryeo Dynasty; r. 1351-1374).

Jongmyo is a supreme architectural monument rich in political and religious symbolism, built by top-class architects and engineers of the past dynasty. The royal pantheon embodies the unique spiritual value and ritual decorum of a Confucian monarchy. Yet, it is far from ornate or extravagant.

With the minimum space necessary for ancestor veneration and characterized by highly refined simplicity minimizing color and ornament, the shrine is a thought-provoking place that prompts reflection about the passage of time and eternity as well as generational repetition and transmission. As the everyday sounds vanish, it feels like time has stopped to open another world. The solemn depth transcending time and space overwhelms the visitor.

※ Reservation or other inquiries, please contact here : ☎ +82.2.2174.3636

|

>

>